What is the point? – if not to see what the function of the other, of the human other, is, in the adequation of the imaginary and the real.

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan – Book I – Freud’s paper on Technique (1953-1954), Trans. John Forrester, Norton Paperback, New-York, 1991, p. 139 – 140

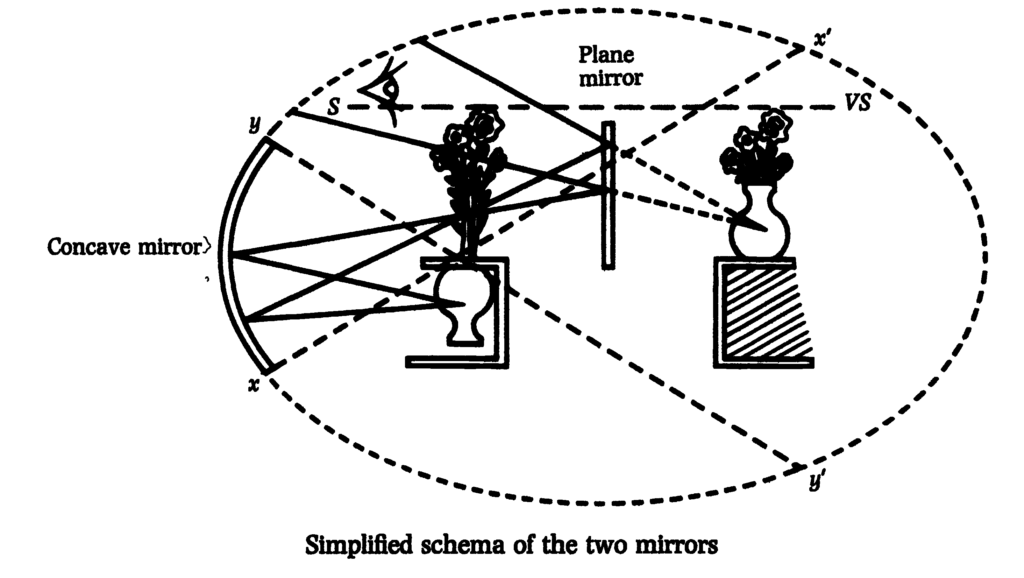

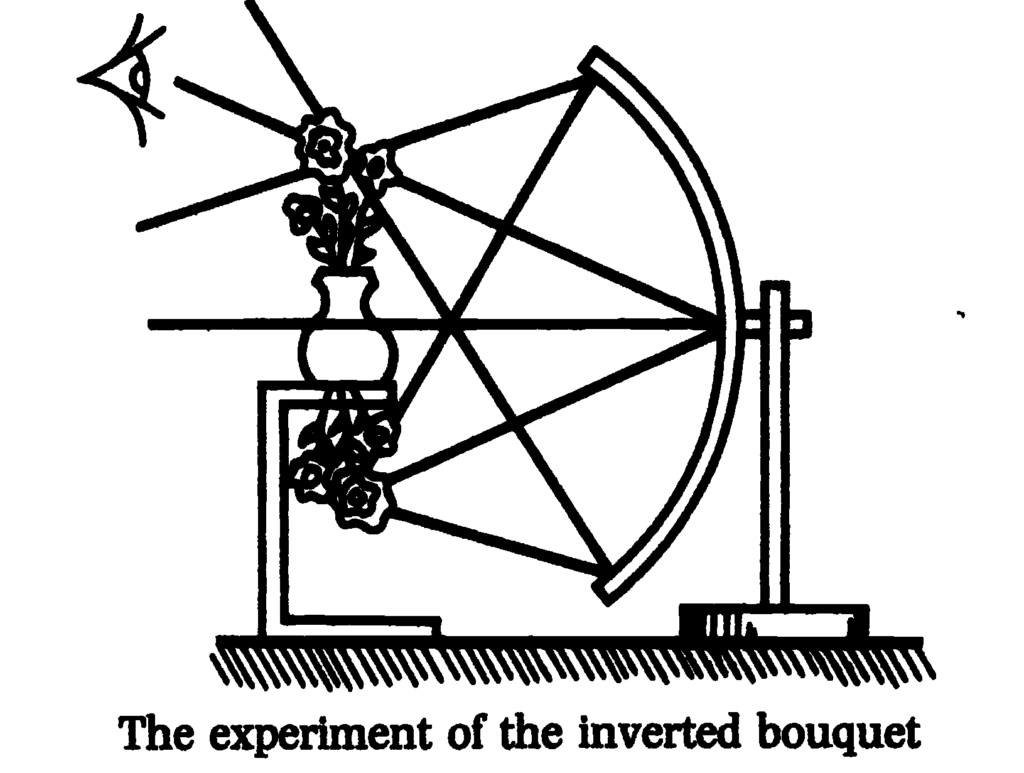

Here we’ll take up the little schema again. The finishing touch I added to it in our last session constitutes an essential element of what I am trying to demonstrate. The real image can only be seen in a consistent fashion within a limited field of the real space of the apparatus, the field in front of the apparatus, as constituted by the spherical mirror and the inverted bouquet.

We have placed the subject at the edge of the spherical mirror. But we know that the seeing of an image in the plane mirror is strictly equivalent for the subject to an image of the real object, which would be seen by a spectator beyond this mirror, at the very spot where the subject sees his image. We can therefore replace the subject by a virtual subject, VS, placed inside the cone which limits the possibility of the illusion – that’s the field x’y’. The apparatus that I’ve invented shows, then, how, in being placed at a point very close to the real image, one is nevertheless capable of seeing it, in a mirror, as a virtual image. That is what happens in man.

What follows from this? A very special symmetry. In fact, the virtual subject, reflection of the mythical eye, that is to say the other which we are, is there where we first saw our ego – outside us, in the human form. This form is outside of us, not in so far as it is so constructed as to captate sexual behaviour, but in so far as it is fundamentally linked to the primitive impotence of the human being. The human being only sees his form materialised, whole, the mirage of himself, outside of himself.

De quoi s’agit-il? – sinon de voir quelle est la fonction de l’autre, de l’autre humain, dans l’adéquation de l’imaginaire et du réel.

Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire – Livre I – Les écrits techniques de Freud (1953-1954), Le Seuil, 1998, p. 220 – 221

Nous retrouvons là le petit schéma. Je lui ai apporté à la dernière séance un perfectionnement qui constitue une partie essentielle de ce que je cherche à démontrer. L’image réelle ne peut être vue de façon consistante que dans un certain champ de l’espace réel de l’appareil, le champ en avant de l’appareil constitué par le miroir sphérique et le bouquet renversé.

Nous avons situé le sujet sur le bord du miroir sphérique. Mais nous savons que la vision d’une image dans le miroir plan est exactement équivalente pour le sujet à ce que serait l’image de l’objet réel pour un spectateur qui serait au-delà de ce miroir, à la place même où le sujet voit son image. Nous pouvons donc remplacer le sujet par un sujet virtuel, SV, situé à l’intérieur du cône qui délimite la possibilité de l’illusion – c’est le champ x’y’. L’appareil que j’ai inventé montre donc qu’en étant placé dans un point très proche de l’image réelle, on peut néanmoins la voir, dans un miroir, à l’état d’image virtuelle. C’est ce qui se produit chez l’homme.

Qu’en résulte-t-il? Une symétrie très particulière. En effet, le sujet virtuel, reflet de l’œil mythique, c’est-à-dire l’autre que nous sommes, est là où nous avons d’abord vu notre ego – hors de nous, dans la forme humaine. Cette forme est hors de nous, non pas en tant qu’elle est faite pour capter un comportement sexuel, mais en tant qu’elle est fondamentalement liée à l’impuissance primitive de l’être humain. L’être humain ne voit sa forme réalisée, totale, le mirage de lui-même, que hors de lui-même.

Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire – Livre I – Les écrits techniques de Freud (1953-1954), Le Seuil, 1998, p. 220 – 221