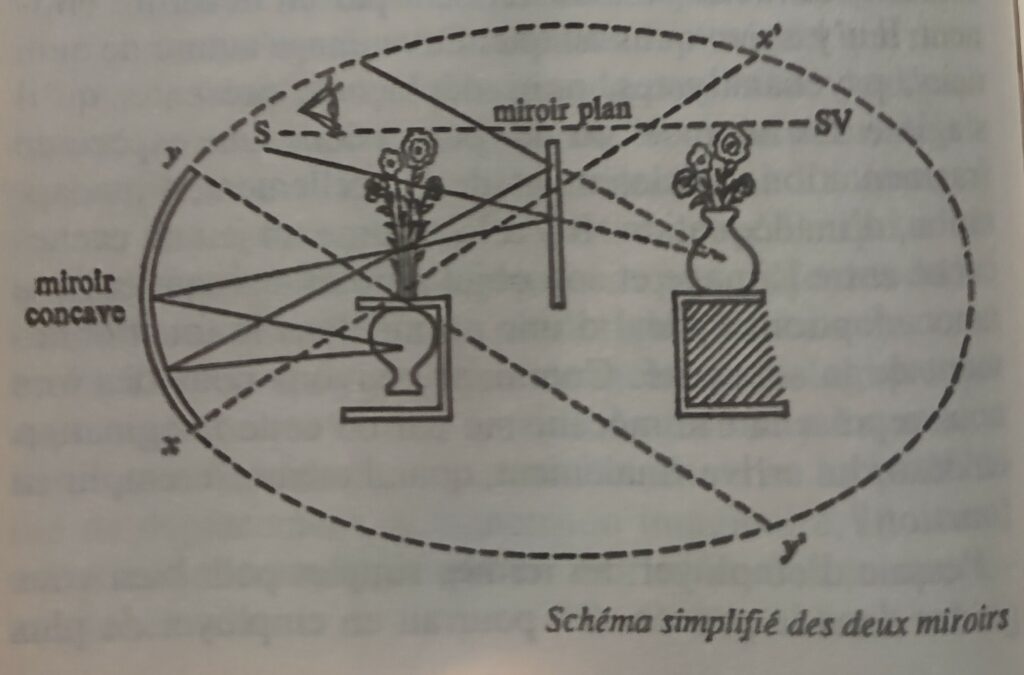

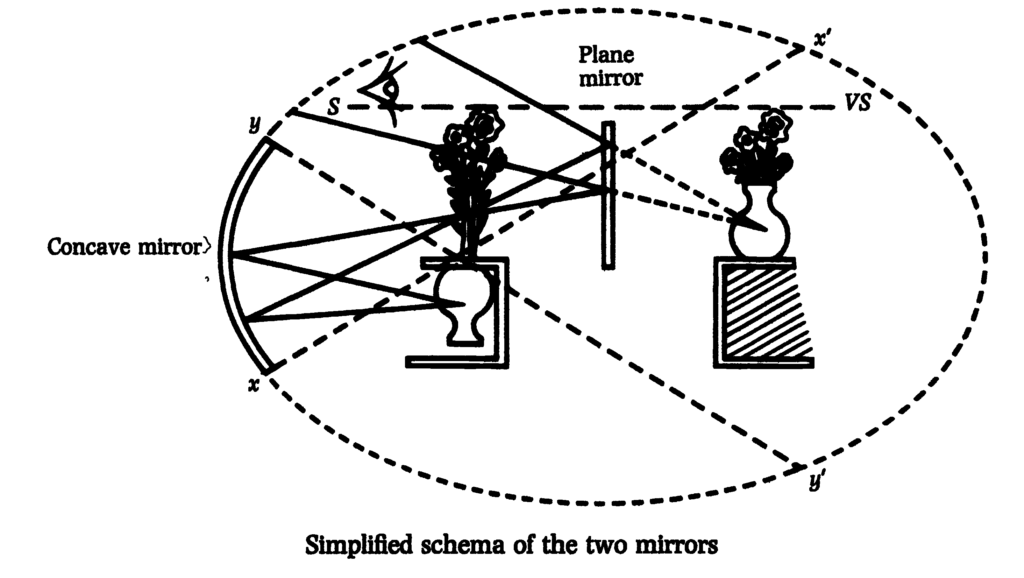

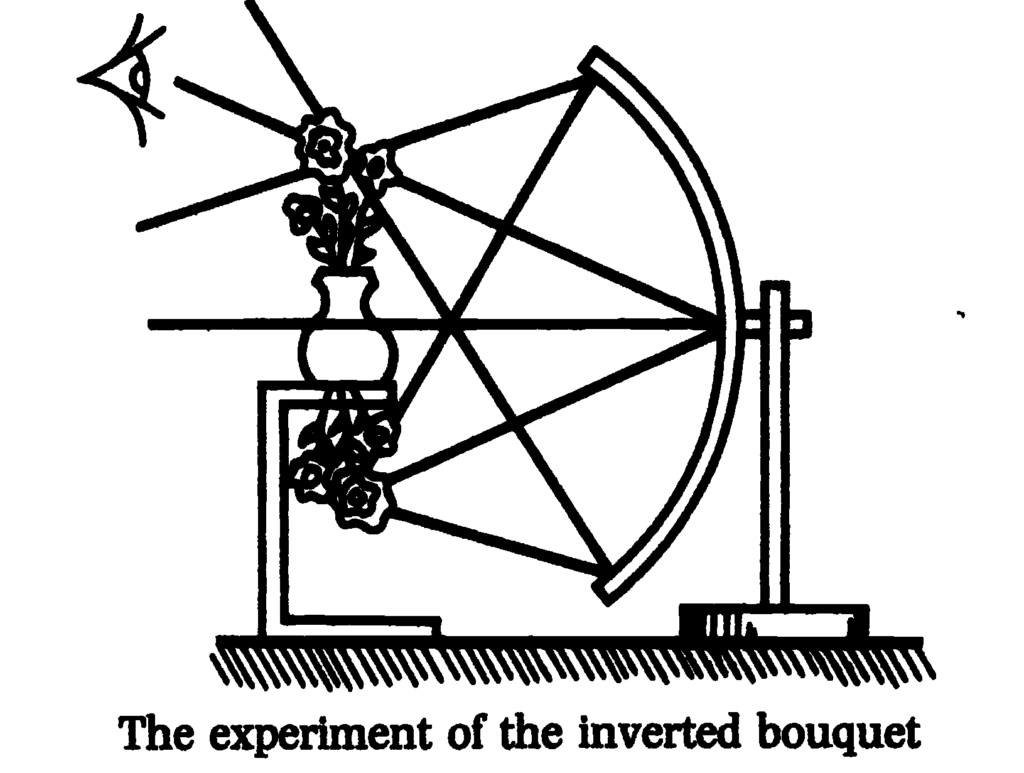

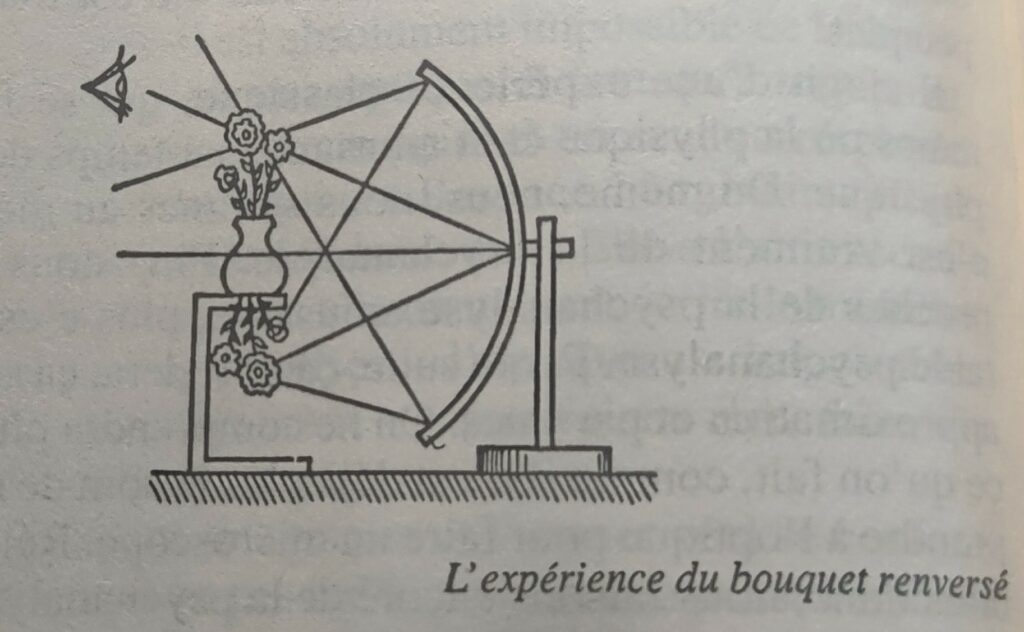

A schema like this one shows you that the imaginary and the real act on the same level. To understand this, all we have to do is to make another little improvement in the apparatus. Think of the mirror as a pane of glass. You’ll see yourself in the glass and you’ll see the objects beyond it. That’s exactly how it is – it’s a coincidence between certain images and the real. What else are we talking about ,when we refer to an oral, anal, genital reality, that is to say a specific relation between our images and images? This is nothing other than the images of the human body, and the hominisation of the world, its perception in terms of images linked to the structuration of the body. The real objects, which pass via the mirror, and through it, are in the same place as the imaginary object. The essence of the image is to be invested by the libido. What we call libidinal investment is what makes an object become desirable, that is to say how it becomes confused with this more or less structured image which, in diverse ways, we carry with us.

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan – Book I – Freud’s paper on Technique (1953-1954), Trans. John Forrester, Norton Paperback, New-York, 1991, p. 141

So this schema allows you to represent to yourself the difference which Freud always carefully drew, and which often remains puzzling to readers, between topographical regression and genetic, archaic regression, regression in history as we are also taught to designate it.

Un tel schéma vous montre que l’imaginaire et le réel jouent au même niveau. Pour le comprendre, il suffit de faire un petit perfectionnement de plus à cet appareil. Pensez que ce miroir est une vitre. Vous vous voyez dans la vitre et vous voyez les objets au-delà. Il s’agit justement de cela – d’une coïncidence entre certaines images et le réel. De quoi d’autre parlons nous quand nous évoquons une réalité orale, anale, génitale, c’est-à-dire un certain rapport entre nos images et les images? Ce n’est rien d’autre que les images du corps humain, et l’hominisation du monde, sa perception en fonction d’images liées à la structuration du corps. Les objets réels, qui passent par l’intermédiaire du miroir et à travers lui, sont à la même place que l’objet imaginaire. Le propre de l’image, c’est l’investissement par la libido. On appelle investissement libidinal ce en quoi un objet devient désirable, c’est-à-dire ce en quoi il se confond avec cette image que nous portons en nous, diversement, et plus ou moins, structurée.

Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire – Livre I – Les écrits techniques de Freud (1953-1954), Le Seuil, 1998, p. 223

Ce schéma vous permet donc de vous représenter la différence que Freud fait toujours soigneusement, et qui reste souvent énigmatique aux lecteurs, entre régression topique et régression génétique, archaïque, la régression dans l’histoire comme on enseigne aussi à la désigner.

Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire – Livre I – Les écrits techniques de Freud (1953-1954), Le Seuil, 1998, p. 223